By Bill Sherman

Before white settlers transformed a wilderness prairie into a state that would become the argicultural capital of the United States, it belonged to American Indian tribes like the Sac and Fox, often called the Sauk and Meskwaki, while leaders like Keokuk, Black Hawk and Poweshiek ruled its land.

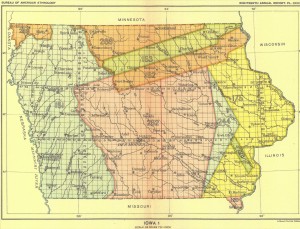

The U.S. Government used nine treaties to remove American Indians from Iowa as seen on this 19th century map.

All of that would change, as history has taught us, through a series of 368 treaties and executive orders used by the U.S. government from 1776 to 1886 to seize more than 1.5 billion acres from America’s indigenous people. Some historians call it the largest land grab in the world, which led to the formation of states like Iowa.

So what were the terms of the treaties? How much money was exchanged? What were the boundaries? How did they shape Iowa?

“The treaty pattern established by British, French and Dutch colonies was used in part because some tribes were more powerful than the U.S. government which was born broke and tired from the battle for independence,” said Eric S. Zimmer, a doctoral candidate specializing in American Indian history at the University of Iowa

The federal government used nine treaties to remove American Indians from Iowa. Historians say that the Sac and Fox, often called the Sauk and Meskwaki, held the largest amount of land in Iowa. (Zimmer claims the tribal group has been incorrectly treated as one tribe for nearly 200 years and should be referred to as Sauk/Meskwaki).

The first treaty that required American Indians to cede land in what is now Iowa was signed on Aug. 4, 1824, in Washington, D.C. Ten members of Sauk/Meskwaki agreed to relinquish their claim to the land they possessed in what is now Missouri. The treaty also included a provision referred to as the Half Breed Tract. It was a small 119,000-acre, triangular area between the Des Moines and Mississippi rivers on the southeastern tip of Iowa where the city of Keokuk is located. It was set aside for use by mixed marriage families — usually white men married to American Indian women. The half-breed citizens could live there, but could not buy or sell any of the land.

This arrangement, however, was short lived. In 1834, Congress repealed the Half Breed Tract portion of the 1824 treaty. White claim jumpers, attracted by Iowa’s rich soil began moving into the area as they ran out of farm land east of the Mississippi River.

The first large American Indian land loss in Iowa was triggered by an 1804 document. That year, William H. Harrison, governor of the Indiana territory, completed a series of agreements with representatives from the Sauk/Meskwaki, Fox, Illinois and Delaware tribes. One provision, signed by five Sauk/Meskwaki representatives, required them to relinquish their holdings east of the Mississippi River when white settlers started moving into the area. This would not happen until the early 1830s when white farmers started moving into the territory near where the city of Rock Island, Ill., is now located.

When white farmers arrived, the Sauk/Meskwaki were asked to leave by the Illinois governor. One faction headed by Black Hawk refused. Indian women, who did the farming, pressured him to stay. They complained that the prairie soil west of the Mississippi River in Iowa was too difficult to break with their hoes.

Another faction headed by Keokuk yielded to government demands and agreed to move west across the Mississippi into Iowa. As a result, the U.S. recognized Keokuk as the de facto chief of the Sauk/Meskwaki.

In his book, “The Upper Mississippi Valley: How the Landscape Shaped our Heritage,” historian William Burke explained “The fraud of the 1804 treaty with the Sac and Fox led to the Black Hawk War in 1832.” The war had a significant impact on the Iowa territory even though the battles were fought in what is now Illinois and Wisconsin.

Patrick J. Jung summarized the impact in his book, “The Black Hawk War of 1832.” He noted, “The cost of the four month Black Hawk War to the United States has been estimated at $8 million in 1990 dollars. (For 2015 that figure would increase to roughly $14.2 million according to westegg.com/inflation website.) The causalities included 72 whites and an estimated 450 to 600 Sac. Less than 1,000 Indians battled against 12,000 U.S. Army regulars and the Illinois militia … This was the last major uprising by Indians east of the Mississippi River.”

Following the war, Gen. Winfield Scott forced the Sauk/Meskwaki headed by Keokuk to sign a treaty known as the Black Hawk Purchase on Sept. 21, 1832, across the river from Fort Armstrong, near where Davenport is located. One provision required Sauk/Meskwaki to give up the eastern third of Iowa for their failure to restrain Black Hawk from going to war. The area ranged from the Mississippi River to Elkader on the north, Fort Madison to the south and Iowa City to the west.

The U.S. agreed to pay the Sauk/Meskwaki $20,000 for the next 30 years for the territory. They also provided them with additional blacksmith and gunsmith shops and gave them a yearly allowance of 40 kegs of tobacco, 40 barrels of pork, 50 barrels of flour and 6,000 bushels of corn to prevent starvation.

Black Hawk was imprisoned and his supporters were prevented from serving as tribal leaders. Keokuk was awarded 400 sections of land along the Iowa River for his refusal to go to war and the area was known as Keokuk’s Reserve.

However, Keokuk’s gift was short lived. In 1836, another treaty was signed that forced the Sauk/Meskwaki to give back the land to the U.S. as American Indians were not permitted to live in the area after Nov. 1.

For giving up the reserve, the Sauk/Meskwaki received an annuity of $10,000 for 10 years, plus $30,000. It amounted to about 75 cents per acre. Two years later, the same land was sold to white settlers for $3 per acre.

In 1837, government officials met with Keokuk and a few of his followers in Washington, D.C., to negotiate another treaty. Keokuk soon agreed to relinquish 1.25 million acres of land immediately to the west of the Black Hawk purchase.

For this cession the Sauk/Meskwaki received a $10,000 annuity and $100,000 of their trading debts were forgiven. They also received an additional $67,000 and the funds were used to build mills and provide farming assistance to Sac and Fox remaining in Iowa. The treaty stipulated that all American Indians had to vacate the area within eight months of the treaty date.

According to historian William Hagan, some tribal members felt so betrayed by the treaty that they published a notice in an Iowa newspaper that people should not accept the signature of Keokuk as an “authorized representative of the Indians,” as reported in Hagan’s 1958 book, “The Sac and Fox Indians.”

Perhaps the most unusual Iowa treaty involved moving American Indians into the state temporarily. In the early 1800s, tribes living in Iowa frequently fought against each other. They involved Sioux sub groups (such as Lakota, Nakota and Dakota) opposing the Sauk/Meskwaki in an attempt to control the area. More than 130 tribal leaders from the upper Midwest met at Prairie Du Chien, Wis., on Aug. 19, 1825, and signed a document designed to prevent future tribal conflicts. U.S. representatives headed by William Clark, who had earlier explored the Louisiana Purchase territory for Thomas Jefferson, conducted the council.

Clark told the American Indians that their wars resulted from not having boundaries that defined their territorial rights. Article Two of the 1825 Treaty established the neutral line in the Iowa territory to separate Sioux territory from the area occupied by the Sac and Fox. It ran from northeast Iowa at the Mississippi River and southwest to the Missouri River. The work on the project was completed by the U.S. Deputy Surveyor Captain Nathan Boone, son of Daniel Boone.

The Sioux were to remain north of the boundary line and the Sauk/Meskwaki were to stay to the south, but the fighting between them continued, which led to the development of the Neutral Ground Treaty signed on July 15, 1830.

An agent who represented the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribe, Joseph M. Street, proposed a new approach for the treaty. He suggested moving the Ho-Chunk from what is now southwestern Wisconsin. White farmers and lead miners had rights to purchase and settle lands in this area as a result of an 1804 treaty. Because of this, Street believed the Ho-Chunk could not remain in Wisconsin. He also felt there would be continuing conflict between the Sioux and the Sauk/Meskwaki.

To solve the problem, Street proposed that the U.S. create a neutral zone by purchasing a 20-mile wide section of land along the 200-mile neutral boundary line from both the Sioux and the Sauk/Meskwaki and Fox. He suggested that the Ho-Chunk could be relocated from Wisconsin into this 40 mile wide neutral zone and that they would serve as a buffer between the Sioux and the Sauk/Meskwaki. Even though the Ho-Chunk had maintained peaceful relations with both of these tribes, they were not eager to live between them.

The government agreed to implement Street’s plan and the 40-mile wide neutral zone ran from the Mississippi River to the Des Moines River, or about 200 miles. The Sioux retained their land to the north and south of the neutral ground. The Sauk/Meskwaki received $6,500 and the Sioux $5,000 in annuities for 10 years for the use of their lands.

For giving up their holdings east of the Mississippi River in Wisconsin, the Ho-Chunk received an annuity payment of $20,000 per year. Some of the funds were used to build a school.

But like so many other treaties, the neutral zone arrangement was short lived. The Ho-Chunk were forced to sign another treaty in 1837 to give up the first 20 miles of the neutral ground west of the Mississippi. In 1840, Fort Atkinson was built in northeast Iowa to keep peace between the Sioux and Sac and Fox and to monitor the Ho-Chunk in keeping them from returning to Wisconsin.

When Iowa became a state in 1846, the Ho-Chunk lost their remaining area in the neutral zone. They were relocated to what is now southwestern Minnesota. Officials estimated the cost to the U.S. for implementing the neutral zone was $370,000.

The final treaty with the Sauk/Meskwaki took place in October 1842. This one ceded to the U.S. all Iowa territory between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers held by Sauk/Meskwaki. Their leaders received an annual annuity worth five percent of $800,000 and the U.S. paid tribal trading debts of $258,566.

Two more treaties were negotiated with different tribal groups. The first was with the Potawatomi. It was signed near Council Bluffs in June of 1846. The Potawatomi sold all lands they held in the Iowa territory for $850,000, which ran from the Missouri River to Carroll and north and south from the Minnesota territory border to the Missouri line. The U.S. paid $50,000 for tribal debts and home loss compensation. An additional $70,000 was paid for moving costs and one year’s food subsistence.

The final treaty negotiated with American Indians still living in Iowa was with the Sioux. It was completed at an agency in the Minnesota Territory and became effective on Feb. 24, 1853, years after Iowa had gained statehood in 1846.

The Sioux ceded all lands they owned in northwest Iowa and the Minnesota territory in return for $1.6 million. Deducted from this total was $275,000 given to the chiefs to settle their affairs, including expenses for the removal process, which had to be completed within two years. There was also subsistence funding for one year and $30,000 was to be used to break and fence land, establish farms, build mills and construct blacksmith shops. The balance of $1.3 million remained in a Sioux trust account that generated a five percent payout for 50 years.

Burke notes that the total cost to the U.S. for buying all the territory making up what is now Iowa was nearly $2.9 million, which amounted to about 8 cents per acre. It compares with a price of 3.5 cents per acre the U.S. paid for land in the Louisiana Purchase. As a result, one could argue the U.S. treated American Indians better than the French government did.

However, the story of land transfer between the government and American Indians who lived in Iowa does not end there.

In the early 1850s, a contingent of Sauk/Meskwaki Indians returned to Iowa from Kansas. They reunited with some tribal members who had never left the state and decided to attempt to buy back some of the land they once occupied. By working with local citizens, the governor and state legislators, they were able to purchase an 80 acre settlement in Tama County along the Iowa River. In 1856, the Iowa General Assembly approved legislation allowing the Meskwaki to own this land and they urged the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs to recognize the purchase and to continue their annuity payments.

This may have been the first time American Indians were allowed to buy land in the U.S. The price was $12.50 per acre, much higher than the 10 cents per acre the U.S. paid the Sac and Fox for the same land in 1832.

Consequently, the U.S. Government Bureau of Indian Affairs refused to recognize the land sale and they stopped annuity payments. They claimed it was illegal for American Indians to own land in the U.S., but the Sauk/Meskwaki quest for self-governance would continue to move forward and succeed. By 2014, more than 1,000 Meskwaki were living on the 7,800 that they own in Tama County, according to figures on the Meskwaki website.

In “The Worlds Between Two Rivers,” Edward Purcell described the Meskwaki land acquisition as the “major story of American Indians in Iowa history … By purchasing and holding title to land they were able to avoid many of the destructive federal policies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Because the lands were private property, the Sauk/Meskwaki were able to construct a cultural and ethnic enclave in the heart of white, agricultural Iowa. As a result, they preserved to a remarkable degree the integrity of their native, cultural, political and social institutions.”

TO READ MORE ABOUT THIS STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal. You can also purchase back issues at the store.