Celina Karp Biniaz, one of the last living survivors from Schindler’s list, holding one of the pairs of scissors her family received from Oskar Schindler’s factory to barter shortly before they were liberated after World War II. The Holocaust survivor kept this pair of scissors for decades and is pictured on the day she donated them in 2019 to the Iowa Jewish Historical Society, Tifereth Israel Synagogue, in Des Moines. Inspired by Steven Spielberg’s 1993 movie “Schindler’s List” to speak publicly about her Holocaust experience she said, “Oskar Schindler gave me my life, but Steven Spielberg gave me my voice.” Photo courtesy of the Iowa Jewish Historical Society

July/Aug 2024 (Volume 16, Issue 4)

By William Friedricks

Shortly after Celina Karp Biniaz began her senior year at North High School in Des Moines, the Des Moines Tribune ran a front-page article about her, describing her Holocaust experience during World War II, including an encounter with the notorious German SS officer and physician Josef Mengele, the Nazi’s so-called “Angel of Death,” at Auschwitz concentration camp.

The 13-year-old Celina was among a group of women ordered to strip naked and parade before Mengele, who determined who would live and who would die in the gas chamber. As Celina passed by, he directed the skinny teenager to the side to be executed. But he then ordered the women to walk by again, and when Celina reached him this second time, she found the courage to say, “Let me go.” Remarkably, he did, and Celina survived.

The newspaper story led the school’s drama club to adapt events in Celina’s life into a radio drama, emphasizing the Mengele incident. The program aired on Des Moines’s KRNT radio station.

Despite this apparent interest in her recent past, Celina quickly learned what other survivors had concluded: most people could not comprehend the Holocaust and did not want to hear about it. She therefore stopped discussing it, keeping it secret for nearly five decades until Steven Spielberg’s film, “Schindler’s List,” was released in 1993.

The award-winning movie provided historical context for the Holocaust, and for Celina, a real-life member of Schindler’s list, it opened the door for her to discuss this part of her life.

Celina was born on May 28, 1931, to Phyllis and Irvin Karp in Kraków, Poland. The family was among the city’s 56,000 Jews, a quarter of its population. Both her parents worked in the accounting field, and the Karps had a comfortable apartment in a middle-class neighborhood.

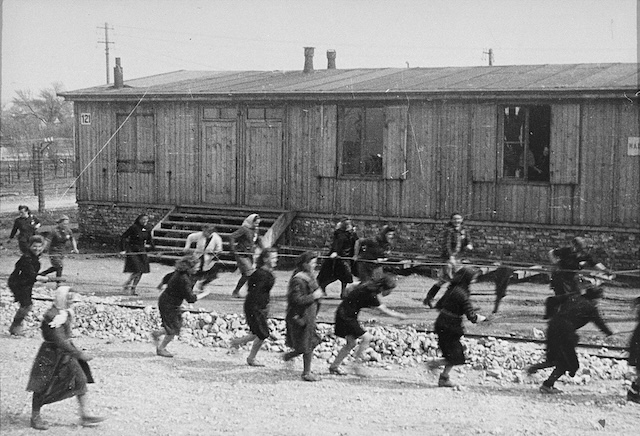

Jewish women at forced labor camp at Płaszów. Behind them is a barrack owned by Julius Madritsch’s clothing firm, where Celina and her parents worked, 1943-1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Leopold Page Photographic Collection

Here Celina enjoyed “a wonderful childhood.” She had lots of friends, loved school, took ballet lessons, and spent time at the local movie theater, where in 1939, for instance, she saw Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

But that September, Celina’s life was upended after the Germans invaded Poland. The Nazis rapidly consolidated their control, and Jewish life became increasingly circumscribed. Jews began losing their civil rights, and they were immediately banned from school, so Celina never started third grade.

Things grew worse. In March 1941, Celina, her family, and the rest of Kraków’s 15,000 remaining Jews were forced into the ghetto, a 12-block section of a city suburb. The area was cordoned off with barbed-wire fencing and walls capped with arches that resembled Jewish tombstones.

Conditions were cramped. Celina, her parents, and an aunt and uncle were assigned one room of a two-room apartment, another family lived in its kitchen, and a third family resided in the other room.

But the Karps spent as much time as possible inside their room because the ghetto streets were dangerous, with Jews facing daily attacks from Nazi guards. Work was a respite from these threats, and here Celina’s parents enjoyed some good fortune.

Before the war, Irvin had become a manager of Hogo, a Jewish-owned apparel factory; Phyllis later joined the company in the fall of 1939. After Poland fell, the firm and other Jewish businesses were taken over by German trustees. Julius Madritsch, a Viennese businessman in the textile industry, was charged with running Hogo. He soon gained a reputation for being good to his Jewish workers and provided them with extra food and medication.

Celina Karp Biniaz with her parents, Phyllis and Irwin Karp, in Des Moines, circa 1950. Photo courtesy of Celina Karp Biniaz

Greed drove another opportunistic businessman named Oskar Schindler to Kraków as well, where he took over an enamelware company. But over the course of World War II, Schindler developed a compassion for his Jewish workers; this eventually led to the now famous Schindler’s list.

That was down the road, however, and neither Irvin nor Phyllis knew Schindler yet, but they felt lucky to work for Madritsch. Although they were protected from Nazi guards while in his factory, they worried about Celina who was left alone in the ghetto each day. Their concerns were well founded. With preparations for the Final Solution—the mass murder of all European Jews—underway by 1942, the Nazis began culling the ghetto population of those who could not work. Celina was too young to have a work permit, and children were increasingly seen as expendable.

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.