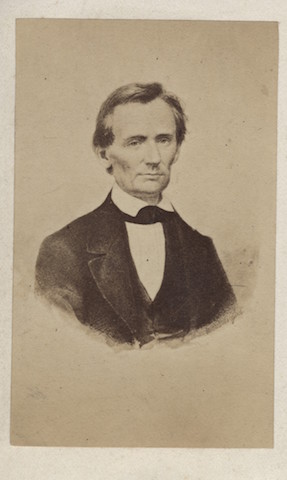

Carte-de-visite of Abraham Lincoln taken by Mathew Brady in his New York studio Feb. 27, 1860, just seven months after Lincoln visited Dubuque in July 1859. Lincoln was in New York giving his famed Cooper Union address. Lincoln claimed his Cooper Union address and this image by Brady got him elected President of the United States. Photo courtesy of John T. Pregler

By John T. Pregler

Living in Dubuque at the time of Abraham Lincoln’s visit on July 16, 1859, was none other than Col. Roswell B. Mason, George B. McClellan’s predecessor as engineer-in-chief of the Illinois Central Railroad Co. Mason had moved to Dubuque in 1856, after completing the Illinois Central, to start construction on the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad, from Dubuque to Dyersville. Mason had signed on as the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad’s chief engineer from the railroad’s founding on April 28, 1853, while he was engineer-in-chief and superintendent of the Illinois Central. Mason and Illinois Central President Robert L. Schuyler were original members of the group of individuals who first incorporated the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad.

Led by Lucius H. Langworthy, an original founder of the city of Dubuque in 1833, the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad was formally incorporated on May 19, 1853. Langworthy was joined by Mason and Schuyler along with Jesse P. Farley, the railroad’s first president; Platt Smith, the railroad’s attorney; Frederick S. Jesup, the railroad’s treasurer and brother of Morris Ketchum Jesup, a prominent New York banker and railroad financier; U.S. Iowa Sen. George Wallace Jones, who was also the railroad’s first chairman of the board; as well as a host of others including, Judge John J. Dyer, F.V. Goodrich, Robert Walker, Robert C. Waples, Edward Stimson, Capt. G.R. West, Dr. Asa Horr and Mordecai Mobley, a Dubuque banker and early settler of Sangamon County, Ill., and friend of Lincoln.

Jones, while serving a term as U.S. Congressional Delegate for the Wisconsin Territory in 1838, was the first person in U.S. Congress to propose appropriating federal funding to build a transcontinental railroad, connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. The idea was based on the request, research and planning done by Jones’ Dubuque constituent, John Plumbe Jr. Plumbe, a civil engineer, helped finance his national campaign to build a transcontinental railroad with profits from his widely successful chain of Plumbe’s National Daguerrian (sic) Galleries and the sale of photographic equipment he manufactured. Plumbe died in 1857, never seeing his dream of a railroad from sea to shining sea realized. Plumbe is buried in Dubuque’s Linwood Cemetery and is considered by many to be the father of American photography and the transcontinental railroad.

Jones next played a critical part in U.S. railroad history when, as a U.S. senator from Iowa, he was successful in amending Sen. Stephan A. Douglas’ Federal Land Grant Act of 1850, which provided federal land to the state of Illinois for the creation of the Illinois Central. Jones’ amendment extended the proposed terminus of the Illinois Central from Galena, Ill., to Dubuque, by way of Dunleith, Ill. The successful passage of Jones’ amendment upset the citizens of Galena and created friction between Douglas and the people of Galena in the 1858 U.S. Senate race. During the U.S. Senate race between Lincoln and Douglas, Douglas accused his fellow senator Jones of underhanded politics in getting the terminus of the Illinois Central extended from Galena to Dubuque in 1850. Jones, a Democrat, took offense to the accusations and came out in public support of Douglas’ Republican opponent, Lincoln, for U.S. Senate in 1858.

Engineer Roswell B. Mason

The Dubuque & Pacific Railroad was conceived as a natural extension of the Illinois Central Railroad, connecting the eastern and western sides of the Mississippi River, allowing the Illinois Central to extend its presence into Iowa and on to the Pacific Ocean and allowing the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad to connect with the markets of the East Coast and the Atlantic Ocean. The plans also called for a railroad bridge to be built across the Mississippi River at Dubuque, connecting the Dubuque & Pacific directly to the Illinois Central. The bridge came close to becoming a reality on Feb. 14, 1857, when the Illinois State Legislature approved a charter for the Dunleith & Dubuque Bridge Co. And engineer Roswell B. Mason was to be the architect of it all. The construction of a railroad bridge was delayed by more than a decade due to the Panic of 1857, the depression that followed and the American Civil War.

Mason moved to Dubuque after resigning as chief engineer from the Illinois Central and the Dubuque & Pacific railroads in 1856. Mason, along with his partner, Ferris Bishop, started Mason, Bishop and Co. in Dubuque, a railroad construction company, which in turn was hired by the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad to prepare the route, build the bridges and lay the tracks for the railroad from Dubuque to Dyersville. Mason, Bishop and Co. was located in the same building as the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad, the Julien Theater building at the northwest corner of 5th & Locust streets. Replacing Mason as chief engineer of the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad in 1856 was one of his associate engineers responsible for building the Illinois Central from Eldina, Ill., near La Salle, to Dubuque — Benjamin B. Provoost.

It is likely that Lincoln and John Moore, along with the state officials, were in Dubuque in July 1859 to meet with Mason and Provoost. There is a strong possibility the meeting was preplanned during McClellan’s visit to Dubuque less than three months prior. Mason’s office was only four blocks from where the Lincoln party was staying in Dubuque at the Julien House and it would not have been the first time Lincoln and Mason had met. Nor would it be the last. Both men had worked at the pleasureof the board of directors of the Illinois Central since the early 1850s.

Mason was a key witness called by Lincoln in his landmark case Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company in 1857. The case revolved around Jacob S. Hurd and his steamboat the “Effie Afton.” Hurd had struck two bridge piers as he tried to navigate the Effie Afton past the first-ever railroad bridge across the Mississippi River, between Rock Island, Ill., and Davenport. The boat was destroyed and the bridge was damaged by the incident. Hurd claimed in his lawsuit that the bridge presented an obstruction to the free navigation of the Mississippi River and therefore the bridge company was responsible for the damages to his steamboat. The Rock Island Bridge Co. hired Lincoln to defend them. Lincoln enlisted the aid of Mason, the eminent railroad engineer living in Dubuque, to help build the defense. Mason testified over the course of two days in the case and described his experience building railroad bridges in the East and throughout Illinois. Mason described a series of tests and experiments he conducted with floats to evaluate the flow and current of the river in relation to the placement of the bridge piers at Rock Island. He related these experiments to piloting a steamboat, navigating the river currents and the ability for railroad bridges and steamboats to successfully coexist in the Mississippi River through intelligent engineering design. It was this testimony that helped Lincoln win this case that was critical to railroads across the nation.

Mason would also go on to be one of three key witnesses Lincoln would call to testify in the Illinois Supreme Court case People v. Illinois Central Railroad in November of 1859. This is the case that led the Lincoln travel party to assess all the properties of the railroad during nine days in July 1859 and the case that lead Lincoln to Dubuque for a two-day stopover with his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and their two sons, Willie and Tad.

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.