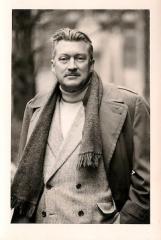

MacKinlay Kantor reached the pinnacle of success and fame as the author of “Andersonville,” a novel about the notorious Civil War prisoner of war camp in Georgia. He is pictured here in the mid-1950s. Photo courtesy of Tom Shroder

By Timothy Walch

“My mother told me that when she and her brother, my uncle Tim, were growing up their father led them to believe that he was the most famous writer who ever lived.” So begins a memoir about the novelist MacKinlay Kantor, written by his grandson, Tom Shroder. It’s a book that captures the rise and fall of one of Iowa’s best-known writers. Fame, as Shroder explains, could be fitful and fleeting and that was manifest in his grandfather’s life and career.

That he would become a famous writer was hardly ordained when Benjamin McKinlay Kantor arrived in this world on Feb. 4, 1904, the son of John Milton Kantor and Effie McKinlay Kantor. He was born in his mother’s hometown of Webster City, the county seat of Iowa’s Hamilton County. Although he traveled widely and lived most of his life away from the state, Iowa remained an important element in his life.

And his Iowa years were a struggle, to say the least. His father abandoned the family shortly after his son’s birth and provided only fitful support in subsequent years. Aided by her own family, Effie found work first as a nurse and later as a newspaper editor. Young Ben was raised and educated in Webster City where he later worked for his mother as a cub reporter. In his teen years he dropped his first name and changed the spelling of his middle name to “MacKinlay” in honor of his grandfather’s Scottish heritage. He was known as “Mack” by his family and friends.

Kantor was largely self-educated and remembered his years in Webster City with nostalgia. He later joked that the local public library was his alma mater. He also learned how to write while working for his mother on the Webster City Daily News. Restless for advancement and adventure, he moved to Chicago in 1925 where he worked as a free-lance writer for several publications including the Chicago Tribune. It was during this stint that he met and married Irene Layne.

Full-time employment as a reporter brought Kantor back to Iowa in 1927 and over the next five years, he worked for newspapers in Cedar Rapids, Des Moines and Webster City. Simultaneously, he embarked on a career as a novelist. By 1932, he had written and published three well-received novels, but none was a commercial success.

He achieved both critical and commercial success as a writer in 1934 with the publication of “Long Remember,” a novel about the Battle of Gettysburg. Critics gushed with praise and compared the book to Stephen Crane’s classic, “The Red Badge of Courage.” More important, Kantor sold the rights to the book to Paramount Productions in Hollywood and began a new career as a screenwriter. Although “Long Remember” never made it to the silver screen, Kantor did find some financial security for the first time in his life.

The next decade was both tumultuous and productive. Kantor wrote more than a dozen books and numerous screenplays during those years. During World War II, he flew multiple bomber missions as a war correspondent for the Saturday Evening Post and continued his work as a screenwriter. And as the war was coming to a close, Kantor wrote a “free-verse novel” titled “Glory for Me” that was the basis for “The Best Years of Our Lives,” one of the great motion pictures on the impact of war.

The impact of war remained a constant theme in Kantor’s work in the years after World War II. He continued to write novels and works of nonfiction, and most received good reviews. In addition, he was a war correspondent in Korea, a special correspondent to the New York Police Department and worked with the U.S. Air Force on issues of personnel, equipment and training operations. He was awarded a “Medal of Freedom” for his work on behalf of the military.

But all this achievement and adventure did not pay the bills. Kantor had an apartment in New York City and a home in Florida and he spent money as fast as he earned it. By 1953, he reported that he was close to broke and needed a project that would change the course of his life. Once again, he turned to war, specifically man’s inhumanity to man. He recalled stories he had heard from Civil War veterans living in Webster City and determined to write a big book about a horrible prisoner of war camp called “Andersonville.”

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.