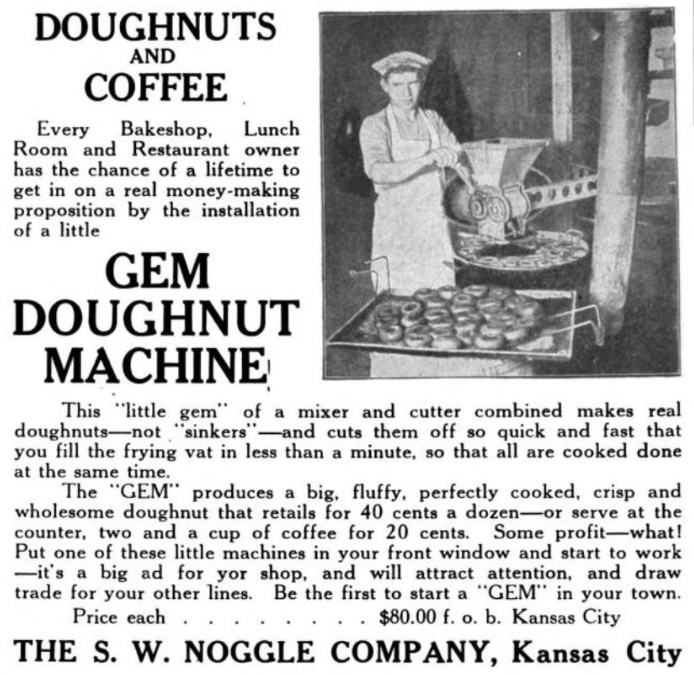

A dour-faced baker appeared in trade publication advertisements for the Gem Doughnut Machine, like this example from 1919.

Sept/Oct 2022 (Volume 14, Issue 5)

By Tim Harwood

Slathered in chocolate, coated in powdered or granular sugar, accessorized with peanuts, coconut, or an array of sometimes sweet, sometimes savory toppings … no matter how a doughnut is dressed, it is instantly recognizable. Millions of doughnuts are eaten every day in the U.S., dating back to the earliest depths of living memory. In 1820, author Washington Irving made one of the first literary references to the treat while telling the story of Ichabod Crane and his headless pursuer in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” A century later, The Salvation Army began to claim a degree of credit for popularizing doughnuts after providing them to U.S. soldiers during World War I. Many other individuals and businesses have sought notoriety for innovations — mechanical and artistic — which have provided the doughnut with a modern universality.

A small Waterloo business deserves recognition for its contribution which helped spread doughnuts across the landscape. Today, the Gem Doughnut Machine Co. is largely forgotten, as are the entrepreneurs behind it. Nonetheless, the designs they patented still form the basis for hardware used to make doughnuts in the 21st century.

Recipes for doughnuts appeared in Waterloo newspapers during the late 1800s. The holey product was on restaurant menus (typically for five cents each, occasionally less), in bakery advertisements, and as a featured item for church fundraising meals. They achieved a degree of popular consciousness, as exemplified by advertisements for unrelated products as far-ranging as paint, health tonics, and early automobiles, each using some variation of the phrase, “We’ll bet dollars to doughnuts…”

Waterloo was industrializing at this time. Located at a hub of three railroads and surrounded by farm country, the community was well-positioned to develop and transport products during an era of increasing agricultural mechanization. By the final years of the 19th century, a local factory (later purchased by John Deere) had already begun producing the tractors which would become Waterloo’s best-known commodity. Others were making equipment for the dairy and livestock industries, as well as wagons, food, clothing, building materials and more.

In this environment, Albert Baum was working for a wholesale grocery business. His family had moved to the city when Baum was a toddler in 1862. Besides his responsibilities to The Fowler Co., in the 1890s Baum had several outlets for his mechanical capabilities. Albert and his father operated steam-driven boats on the Cedar River, ferrying passengers on picnic excursions. Baum & Son simultaneously managed another technologically advanced venture, a steam carpet-cleaning business. Baum’s leisure interests even involved notable machines of the era, beginning with bicycles and eventually advancing to motor cars.

At age 43 in 1904, he submitted the patent papers for a new doughnut cutting machine amidst challenging personal circumstances. The application was filed days after his father had died. The same week, his eight-year-old daughter had an emergency appendectomy. Shortly thereafter, his wife, Scepta (namesake for one of the Baum & Sons steamers), also underwent a medical procedure (its specific nature was not recorded). Yet the year finished under far happier circumstances; even before the federal patent was formally issued, the contraption which Baum had spent two years designing was already being produced under a contract manufacturing agreement with the Iowa Gasoline Engine Co.

With Baum’s apparatus, a baker placed raw dough into a hopper and turned a crank powering all of the machine’s processes. The moving parts formed the batter into a doughnut shape, slicing rings that fell from the bottom of the machine. Mounted to a wall or other stationary surface on a swinging arm, Baum’s doughnut cutter could be pulled into position directly over a fryer, where the doughnuts would be dropped into different parts of the heated oil’s surface to begin cooking. Baum noted the importance of this technique compared with other means of adding the pastries to the grease, which often led to sticking or scorching. Among the innovations he claimed were the “…means for forcing dough there through … a reciprocating cutter, and a means for varying the position of the whole machine…”

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.