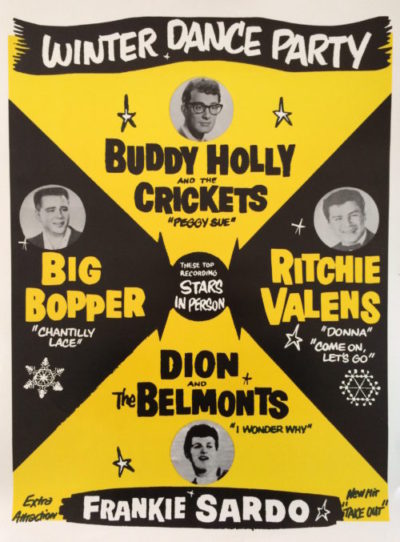

A copy of the 1959 Winter Dance Party poster used to promote shows on the tour. The original version included white space at the top to include information about each venue, showtimes, etc.

By Michael Swanger

Even those who burned records and warned parents about the dangers of their children listening to “devil’s music” could not have foretold a more shocking metaphor for the devitalization of early rock ’n’ roll.

But there it came to be, tragically, in the unlikeliest of places — frozen Iowa farmland near Clear Lake, on Feb. 3, 1959. The body of Mason City pilot Roger Peterson, 21, wrapped around the instrument panel of the red, single-engine, four-seat Beechcraft 35 Bonanza that hit the ground at about 170 mph as the right wing tip gouged the earth for 57 feet before the plane spun into a cartwheel for 540 feet and rested against a barbed-wire fence in a metal heap. Nearby, the bodies of rock ’n’ roll luminaries Buddy Holly, 22, Ritchie Valens, 17, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, Jr., 28, laid among the broken airplane parts and personal effects strewn across the barren land. A dusting of snow fell and drifted against them in the early morning darkness.

The plane crash that killed the stars of the 1959 Winter Dance Party would become known as “The Day the Music Died,” after singer-songwriter Don McLean referred to it in his 1971 folk-rock opus “American Pie,” the longest song to reach No. 1 clocking in at eight minutes and 33 seconds. In 1959, McLean was a 13-year-old New York newspaper boy when he cut open a bundle of papers to be delivered and discovered the awful front page news. It inspired him to write:

But February made me shiver

With every paper I’d deliver

Bad news on the doorstep

I couldn’t take one more step

I can’t remember if I cried

When I read about his widowed bride

But something touched me deep inside

The day the music died

For years, the ambiguous lyrics and pop-culture references in “American Pie” have been interpreted ad nauseam. Most people understand them to be the symbolic death of the mid-century American Dream and early rock ’n’ roll, which by 1959 was reeling from Elvis Presley’s enlistment in the military, the public’s discovery of Jerry Lee Lewis’ “child bride” and Chuck Berry’s imprisonment later that year for transporting a 14-year-old girl across the state line for “immoral purposes.” But it was that fateful night in Iowa that had the most profound effect on the first generation of rock ’n’ roll, the likes of which endure today.

Just as the overarching theme of lost innocence of “American Pie” captured the imaginations of generations of music fans, the tragic plane crash that occurred on Feb. 3, 1959, is ensconced in the annals of popular Iowa history.

Sadly, it is what put our state on the proverbial “rock ’n’ roll map.”

Conversely, it has compelled music fans worldwide to make a pilgrimage to the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, to visit the hallowed hall where Holly, Valens and the Bopper performed their last concert.

The Surf, which was designated as an Historic Rock and Roll Landmark in 2009 by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, has hosted a Winter Dance Party tribute concert every year since 1979. The weekend-long series of concerts are an opportunity for many returning fans to celebrate the music of their youth, honor the legacies of fallen musicians and build friendships. Some even make the late night trek to the crash site after the last show each year to sing dirges in the dark. This year’s celebration, to be held Jan. 31 through Feb. 2, will mark the 60th anniversary of the Winter Dance Party.

With each passing year, as members of the first generation of rock ’n’ roll fade away, legends of the 1959 Winter Dance Party rave on as it continues to be the most widely-reported, intergenerational story in Iowa music history.

Though it has been told often, it is worth telling again.

Check out Winter Dance Party photos in Photo Gallery 1 and Photo Gallery 2.

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal. You can also purchase back issues at the store.