May/June 2023 (Volume 15, Issue 3)

By Michael Swanger

Have you ever wondered how Iowa got its shape? Did you know the process for determining its borders was set in motion by Congress in 1785? Or that slavery played a role in it? Perhaps you’ve heard of the Honey War in 1839, a bloodless territorial dispute with Missouri, but did you know that a portion of our state’s shared border with Missouri remains somewhat “fluid” today?

If you answered “no” to the aforementioned questions, you are not alone. Recent generations of Iowans have learned little of substance about Iowa history before graduating from high school. Fortunately, for young Iowans today, and in the future, the answers to those and other fundamental questions of Iowa history can be found in a digital toolkit for K-12 teachers created by the State Historical Society of Iowa (iowaculture.gov/history). The free, downloadable Primary Source Sets are designed to help Iowa educators meet the Iowa Core Content Anchor Standards for Social Studies and are funded by a grant from the Library of Congress. The materials, however, might appeal to learners of all ages as they did to me.

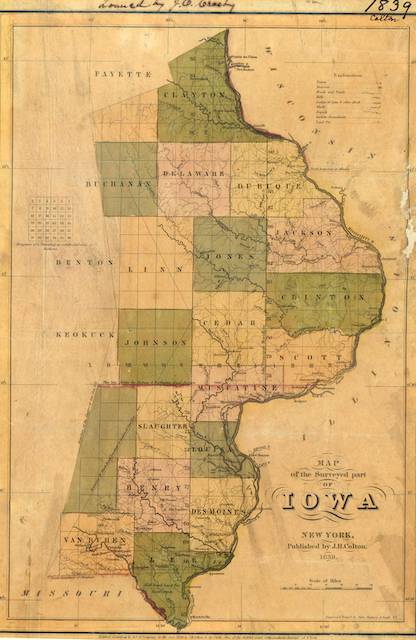

J.H. Colton 1839 map of Iowa. Photo courtesy of State Historical Society of Iowa

Long before President James Polk signed Iowa’s admission bill into law to declare Iowa the 29th state of the Union on Dec. 28, 1846, plans for our beloved state’s shape were set in motion by our nation’s founding fathers and a surveyor named John Sullivan.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 passed by the U.S. Congress under the Articles of Confederation established the process by which lands west of the Appalachian Mountains would be surveyed and sold, creating townships and sections within townships. A region would first become a territory with limited government and when its population reached 60,000 people legislators could ask white males 21 and older to vote on a proposal to create a state constitution to send to Congress along with an application for statehood. In Iowa’s case, a proposal for statehood didn’t pass until 1844 and it would take two more years before voters and Congress would agree upon one.

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, as well as several treaties with American Indians in the early 19th century in which they ceded land, and the War of 1812, Sullivan was commissioned in 1816 to conduct a survey to distinguish a boundary between lands owned by American Indians and the U.S. from Iowa to Texas. His work would influence subsequent surveys and establish the “Sullivan Line” which formed three-quarters of the border between Iowa and Missouri and led to the Honey War.

The Honey War in 1839 between the Iowa Territory and Missouri was a dispute over a nine-mile-wide strip of land caused in part by the muddled wording of Missouri’s constitution and a misunderstanding of treaties and the survey of the Louisiana Purchase. Specifically, it involved the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi River just south of Fort Madison where Sullivan placed markers near Sheridan, Mo., to establish the northwest corner of Missouri, extending the Sullivan Line eastward to the Des Moines River just south of Farmington in Iowa. Confusion over the terms “Des Moines Rapids” on the Mississippi River and the phrase “rapids on the Des Moines River” contributed to a legal entanglement between the two parties as there were several sets of rapids. Even today, as the Missouri River sometimes shifts its flow, issues regarding the border arise.

Ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Iowa’s favor in 1849, 10 years after militias from both states faced off after tax agents from Missouri tried to collect taxes on what is now Van Burn and Davis counties. The taxmen allegedly chopped down three honey bee trees in what is now Lacey-Keosauqua State Park to collect honey as partial payment. Iowans wielding pitchforks chased them away and captured the sheriff of Clark County, Mo., and jailed him in Muscatine.

To add to the border crisis, Iowa’s admission into the Union became fodder for “geo-political bickering” regarding the issue of slavery. Since each state gets two senators, northern states wanted to carve out smaller states on the northern prairies and Great Plains to gain legislative power while pro-slavery southern states favored bigger states in the region.

What’s more, Iowa’s first territorial governor, Robert Lucas, wanted our state to extend as far north to what is now Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minn. A proposed state constitution that eventually failed also redrew the western border about 80 to 100 miles east of the Missouri River. Can you imagine Rochester and Albert Lea located in Iowa? Or Council Bluffs, Sioux City and Storm Lake in Nebraska?

In 1857, Iowa voters approved our state constitution that defines the borders as we know them today. You can look it up.

TO READ MORE FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal. You can also purchase back issues at the store.