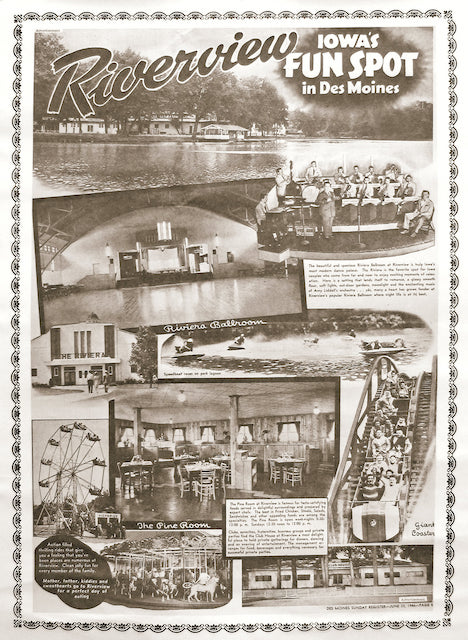

This 1946 advertisement in the Des Moines Sunday Register depicts the variety of entertainment offered by Riverview Amusement Park in Des Moines, from dining and dancing, to speedboat races and carnival rides. Photos courtesy of Riverview Amusement Park Des Moines Iowa (Official Group) Facebook

July/Aug 2023 (Volume 15, Issue 4)

By John Busbee

Clacking tracks, ringing bells, squeals of joy — or, terror. These were the sounds that echoed for decades along a bucolic oxbow on the Des Moines River. Families, young adventurers and wooing couples left their work-a-day worlds behind, and entered the fantasy land that was Riverview Amusement Park in Iowa’s capital city. Those and many more sounds still reverberate in the memories of those who entered the welcoming gates of Riverview Park on Des Moines’ north side.

Why do specters from an iconic amusement park warmly comfort our collective souls, much like the whiff of fresh-baked bread whisks us back to our grandmother’s kitchen? To understand, begin at Riverview Park’s birth in 1915.

A vision begins in Brooklyn

Immigrant energy was an especially dynamic force across the U.S. around 1900. Iowa has an abundance of entrepreneurial success stories from this flood of fresh energy, and immigrants’ status quickly transitioned into American citizenship and contributions. One such seed of ambition, planted by a Russian Jewish immigrant, grew into an iconic entertainment destination that lasted 63 years.

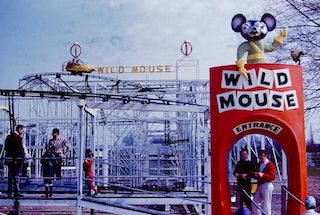

The Wild Mouse roller coaster at Riverview Park

Born in 1872, Abraham “Abe” Frankle was the son of Frances “Fanny” and Henry “Harry” Frankle. This Russian Polish family arrived in New York City in the 1890s. Abe would move west to Cedar Rapids, before his final stopping point of Des Moines in 1906. Abe’s relatives and contacts there would help him transition into a dynamic businessman. By 1912, he was well established in Des Moines’ burgeoning entertainment scene, including as co-owner of the elite Alexandria Club (for gentleman — billiards and bowling); creating a chain of performing halls under his Frankle Theaters brand (the Casino, Rialto and Majestic). He even partnered with A.H. Blank briefly in 1922 in Blank’s Des Moines Theater Co. But that Brooklyn seed planted long before had taken root and started to flourish.

Before his move to Iowa, a younger Abe was mesmerized by the magnificence of an iconic amusement park in New York City. Coney Island Amusement Park in Brooklyn was the largest such operation in the U.S., attracting millions of visitors per year. On its busiest days, it often attracted more than a million visitors in a day. Coney Island’s fame was built on having the newest and best competitor-beating rides and attractions. It was the trendsetter in its field, and the visionary immigrant who would make Iowa’s capital city his home would carry the grandeur and appeal of Brooklyn’s signature entertainment destination with him.

A Coney Island envisioned

In 1912, Abe held an informal meeting with a group of select Des Moines businessmen to explore their level of interest for a new entertainment venue. Des Moines was on the verge of explosive population growth, growing from 62,000 in 1900, to 86,000 in 1910, to 126,000 by 1920. The capital city’s citizens would want options for their leisure time and early amusement park choices were limited. One was in the Grandview area, operated by White City Amusements. The other was in Ingersoll Park, and featured gardens, a band shell and a small wooden roller coaster.

Abe was a savvy businessman and his research showed that Abe Lurie’s Grandview operation was having a hard time paying the bills with the amount of revenue his small park generated. Ingersoll Park was being pressured by builders, who coveted the land at that location for residential development. Abe believed that he needed to build his amusement park at a profitable scale. Those who were at that initial meeting felt that the revenue a seasonal operation would create would not be profitable. Abe was at a stalemate, and the meeting ended with the understanding that if he could secure a fair stakeholder share of the funding needed, the others still wanted to be part of this venture.

Abe was a savvy businessman and his research showed that Abe Lurie’s Grandview operation was having a hard time paying the bills with the amount of revenue his small park generated. Ingersoll Park was being pressured by builders, who coveted the land at that location for residential development. Abe believed that he needed to build his amusement park at a profitable scale. Those who were at that initial meeting felt that the revenue a seasonal operation would create would not be profitable. Abe was at a stalemate, and the meeting ended with the understanding that if he could secure a fair stakeholder share of the funding needed, the others still wanted to be part of this venture.

Abe made a pilgrimage to his entertainment mecca, returning to Coney Island in 1913. This epiphanic visit gave him the insight he needed to launch Riverview. He discovered that Coney Island’s rides and attractions were not owned by Coney Island. This was actually a series of small private groups that paid Coney Island to operate on their location, but within the rules established by the land owner and operator, Coney Island. Abe now was ready to present this new business model to his prospective partners.

As presented by William “Bill” Kooker in his comprehensive history, “Riverview Park: The Lost Summers,” he writes, “…Riverview Amusement Company, Incorporated would furnish the land with basic structures and layout. The rides would be owned and operated by individual ‘small’ companies that would pay rent as well as a percentage of their receipts for the season.

“Abe had a crowning answer to the one question he was expecting, ‘Where are we going to find these renters? We don’t want transient carnival people operating in the park.’” Abe replied with a smile, “I don’t know about you, but this week I’m going to find a group of people to form a ‘Roller Coaster Company’ with me.”

With the spontaneity of a lightning flash, the nine men in the room quickly understood the opportunities and they began planning their own “ride companies” to operate within the park. In 1914, The Riverview Amusement Co. Inc. was formed and the initial stock offering totaling $50,000 was quickly purchased. Those purchasers were:

- Abe Frankle (owner/operator Casino Theatre, Alexandria Club)

- Joseph Muelhaupt (owner Des Moines Ice Co.)

- C.C. Taft (owner C. C. Taft Co., a wholesale distributor of cigars and tobaccos)

- Ira B. Thomas (insurance business)

- Frank C. Walrath (district court reporter)

- Eli Bookey (sales)

- Abe Lurie (owner/operator White City Amusements and several theaters)

- George W. Reel (druggist, real estate)

- Joe Rhynsburger (booking agency and promoter)

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.