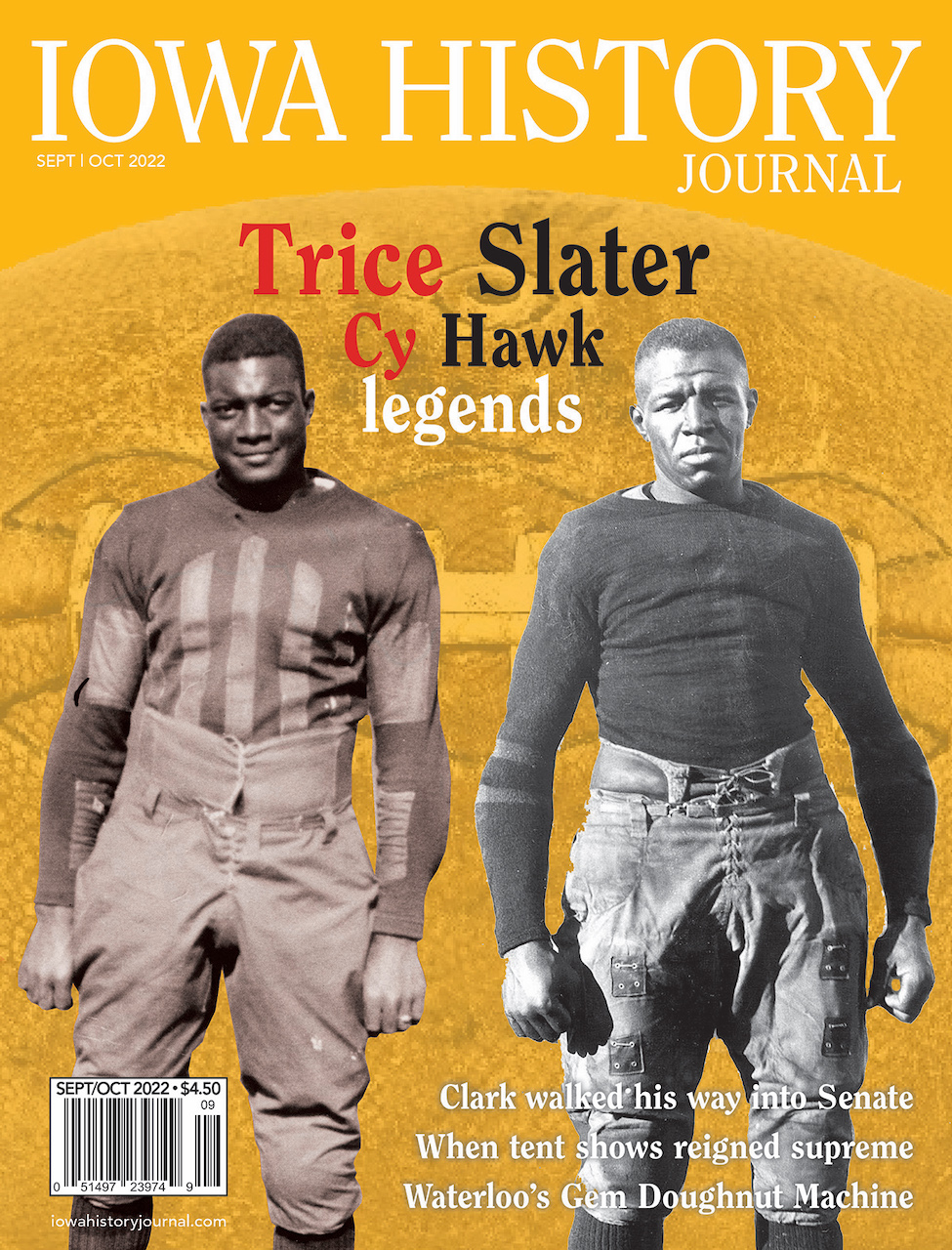

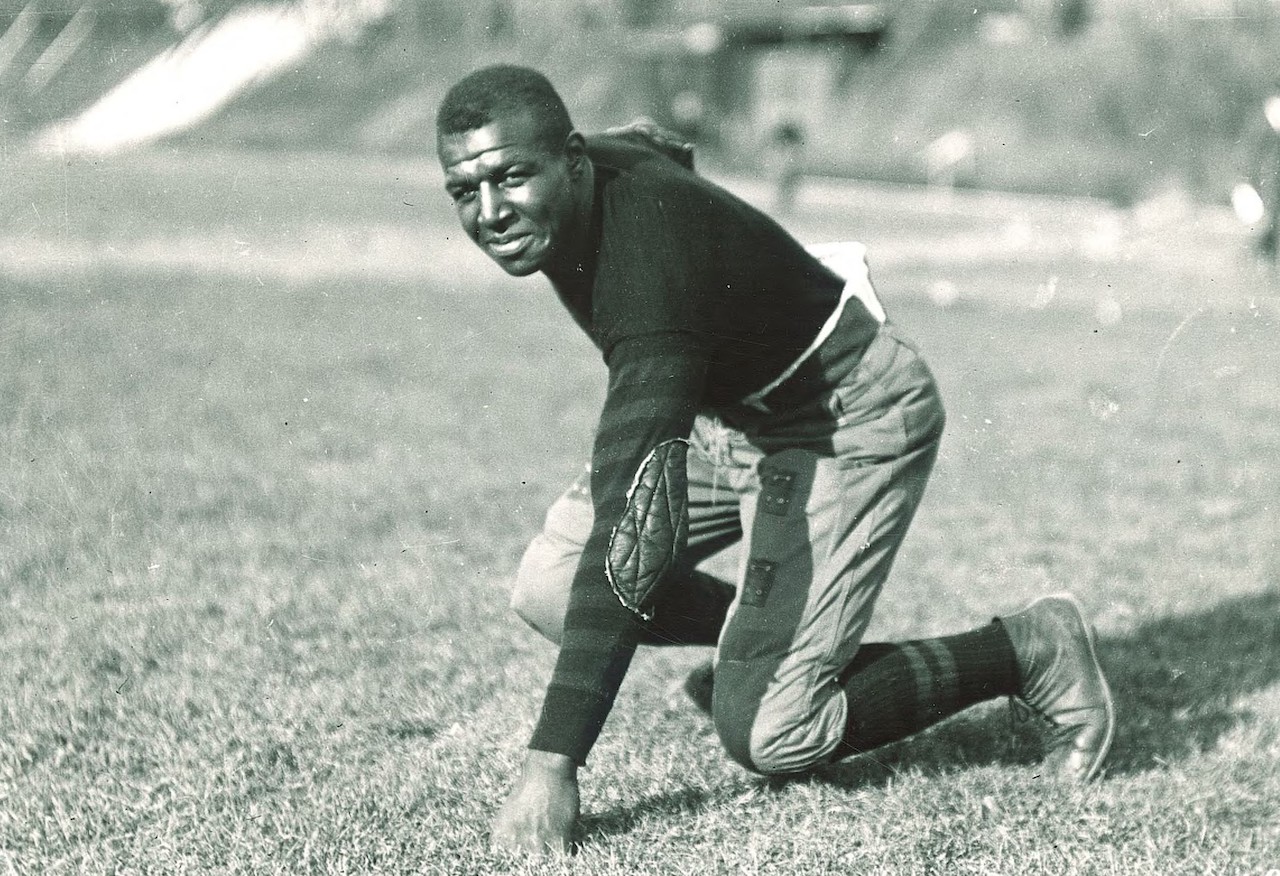

Jack Trice (left) in his Cyclone football uniform, 1923. (Photo courtesy of Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives) Duke Slater (right), All-American Hawkeye, in the early 1920s.

Sept/Oct 2022 (Volume 14, Issue 5)

By Don Doxsie

Frederick Wayman “Duke’’ Slater didn’t begin playing football until his sophomore year of high school in Clinton, but he found out very quickly what it was going to be like to be one of the very few Black athletes playing football at any level more than a century ago.

Slater, who went on to play at the University of Iowa from 1918 through 1921 and spent 10 seasons in the early days of what came to be known as the National Football League, was an obvious target for opposing players. He generally was the only Black player on the field and he took an extreme amount of abuse, both verbal and physical. With only three officials working games in those days, much of the punishment he absorbed went unseen or at least unacknowledged.

Slater never flinched, never complained. He took it all good-naturedly and often joked with opposing players as he picked himself up off the turf. Following one game during his high school career, he was confronted by 50 angry fans in Aurora, Ill., who backed him up against a tree and threatened him with bodily harm. Slater smilingly offered to take on each of them one at a time and somehow defused the situation. The fans finally dispersed.

By all accounts, Jack Trice was the same kind of player and same kind of guy. He became the first Black man ever to play football for Iowa State just a few years after Slater competed at Iowa and although he only played in two games, he experienced the same sort of treatment on the field.

By all accounts, Jack Trice was the same kind of player and same kind of guy. He became the first Black man ever to play football for Iowa State just a few years after Slater competed at Iowa and although he only played in two games, he experienced the same sort of treatment on the field.

Slater and Trice have one other thing in common: Both of their names remain familiar to modern-day fans as the fields on which their alma maters play their games have been named for them. There are only four schools in all of the NCAA’s Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) that have named either their stadium or their playing field for a Black man and two of them are in the state of Iowa.

Iowa State named its field after Trice in 1984 and 13 years later opted to apply his name to the entire stadium. Iowa last year chose to name the field at Kinnick Stadium in tribute to Slater. The only other schools that have made such a move are

Iowa State named its field after Trice in 1984 and 13 years later opted to apply his name to the entire stadium. Iowa last year chose to name the field at Kinnick Stadium in tribute to Slater. The only other schools that have made such a move are  Syracuse, where the playing surface in the Carrier Dome is known as Ernie Davis Legends Field, and Texas, which last year dedicated the field inside Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium as Campbell-Williams Field.

Syracuse, where the playing surface in the Carrier Dome is known as Ernie Davis Legends Field, and Texas, which last year dedicated the field inside Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium as Campbell-Williams Field.

Earl Campbell, Ricky Williams and Ernie Davis earned those honors by winning the Heisman Trophy. Slater and Trice did it by having an even more significant role in their sport, blazing a path so that future African-American athletes could have the opportunity to compete and possibly win the Heisman.

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.