Cyrus Clay Carpenter (right) of Fort Dodge often wrote letters to his fiancé, Susan Catherine “Kate” Burkholder (left), during his military service in the American Civil War. After the war, he became a politician, including serving as the eighth governor of Iowa, 1872-1876. Photos courtesy of State Historical Society of Iowa

May/June 2025 (Volume 17, Issue 3)

By Timothy Walch

Adversity had a way of bonding men in common cause during the American Civil War as noted in their letters from the front lines. That is not to say that frustration and low morale also were uncommon in the Union lines, however. The comments expressed by Capt. Cyrus Carpenter of Fort Dodge were typical.

But Carpenter himself was anything but a typical recruit. A former state legislator, young Carpenter saw the war as an opportunity to serve his country and advance his political career at the same time. He was determined to serve at an appropriate rank and quickly petitioned Gov. Samuel Kirkwood for an officer’s commission. He was denied.

Carpenter would not take this as a final answer, however, and he wrote to both Iowa senators and to his congressman to enlist their support for his cause. Finally, in January of 1862, he received a commission as a “Commissary of Sustenance” with the rank of captain. His mission as to keep Union bellies full so that the troops could fight.

Carpenter had the good fortune to be attached to the Army of the Mississippi under Gen. John Pope and arrived at Pope’s headquarters in Tennessee shortly before the Battle of Shiloh, April 6-7, 1862. He would serve until the end of the war and parlay this service into a successful campaign for governor of Iowa, serving from 1872 to 1876.

Although he had worked hard for his commission and was serving a noble cause, Carpenter was frustrated by the greed and mismanagement that he found among the troops. “One would think that in the present perilous position of our country,” he fumed to his fiancé—Susan Catherine “Kate” Burkholder—in September 1862, “all a soldier would care for, would be to help save the government. But every man from highest to lowest, with few and those very few, exceptions, seem to think this is a money making institution.” Carpenter went on to add that “stealing and the most heinous rascality is so common and so pattent [sic] that I shudder for my country.”

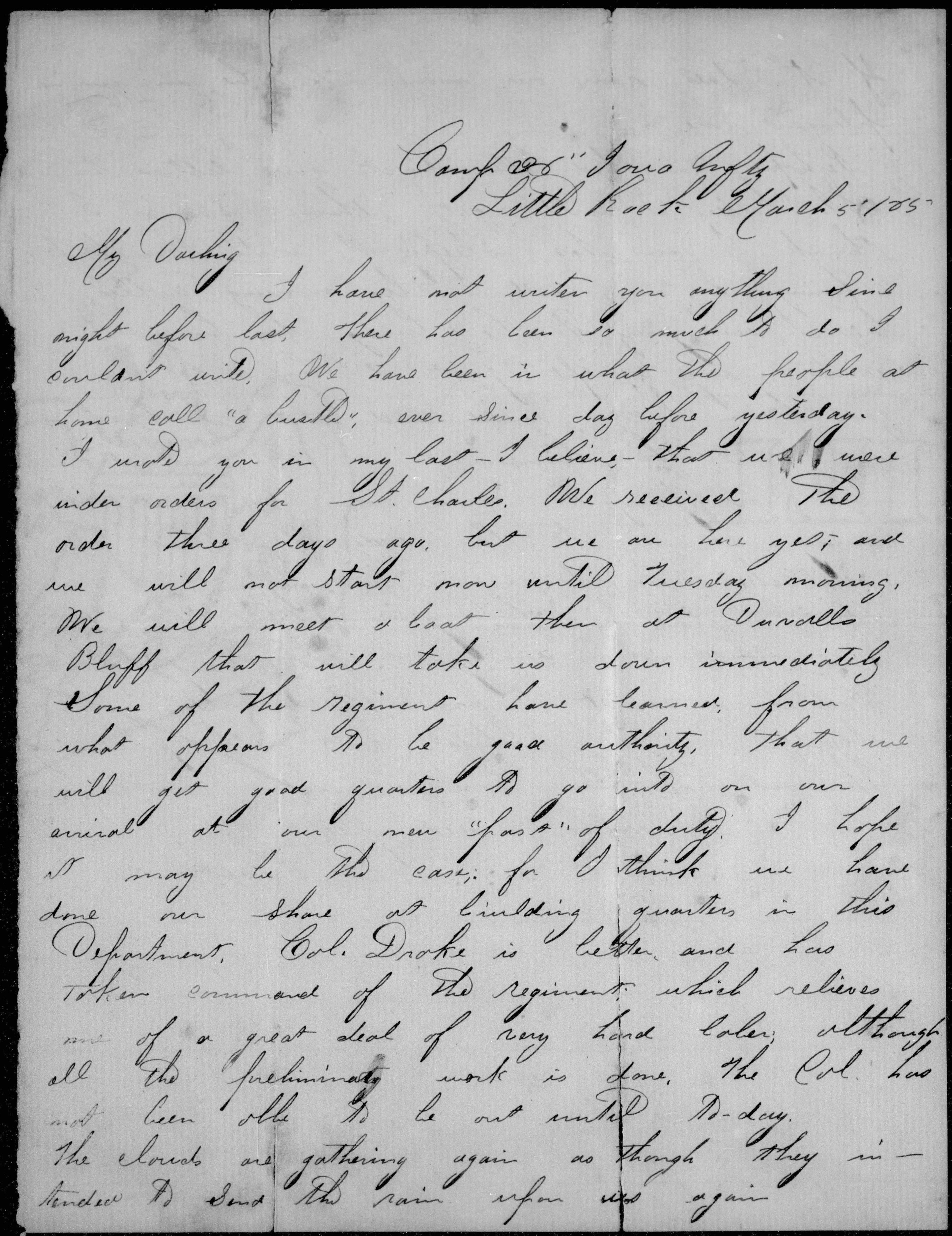

Letters exchanged between William F. Vermillion and his wife, Mary, were published in the book, “Love Amid the Turmoil.” Vermillion was a physician, Civil War company commander in the Union Army, Iowa state senator (1869-73) and lawyer. He was commissioned on Oct. 4, 1862, to command Company F of the 36th Infantry Regiment of Iowa Volunteers, and continued that assignment until his discharge on Aug. 24, 1865. Most of his letters—like this one from March 1865—indicate his location and actions of his regiment stationed near the Mississippi River in Arkansas, as well as daily life in camp. Photo of letter courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library

What Carpenter took from his military experience was that an army not engaged in battle was a sorry lot. On a regular basis he would write to his fiancé that he heard nothing but complaints about the food, shelter and all manner of accommodations. “I should be awful unhappy if I was obliged to stay in a camp with them,” he wrote in March 1863, “and falling upon my ears the continual din of their ten thousand complaints and ceaseless rounds of fault finding oaths.”

Carpenter was not so bitter or critical in letters that he wrote for public consumption, however. For example, in a letter to the Des Moines Register published on Oct. 11, 1864, he went on at length about the confidence that Gen. William T. Sherman seemed to imbue in his troops. “I understood then,” he wrote, “what there is in an army that has perfect confidence in the skill and judgment of its commander. I also had a slight appreciation of that power in a great mind, which by some magnetic influence, can infuse its own enthusiasm into a vast body of men, thousands of whom never saw the man on whom they so implicitly rely.”

Carpenter had seen greatness in Sherman’s March to the Sea in the last two months of 1864 in which Sherman’s troops executed a “scorched earth” policy from Atlanta to the port of Savannah. He also was mindful of what Pope, Sherman and other generals might be able to do for him after the war. Carpenter knew that the war would end someday with a Union victory and he wanted to benefit from that success.

Carpenter’s occasional frustration with military service was well-founded, but he kept his feelings private and expressed them only in his letters to his fiancé. Other Iowa soldiers coped by looking beyond the greed and corruption and focusing on the grand cause in which they were engaged.

A typical expression of this high-minded attitude can be found in the letters exchanged by William F. Vermillion with his wife, Mary. A captain in the 36th Iowa Infantry, Vermillion mustered into service in August 1862 and wrote to his wife less than a month later to say that “my love for you all has increased since I left you, but I know that it is my duty to stay here and try to be one of the many that God has raised to put down this rebellion and blot out the institution of slavery.”

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal.