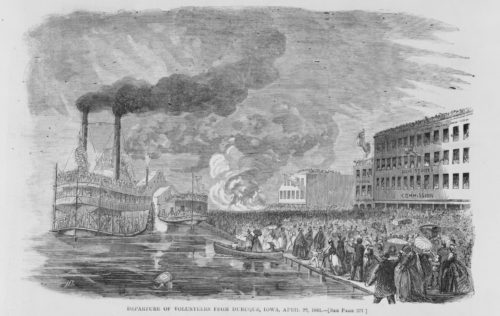

Dubuquers were among the first Iowans to join the war effort. Harper’s Weekly took note of the embarkation of Iowa troops on April 22, 1861. Illustration courtesy of the Center for Dubuque History

By Timothy Walch

There is no question that the Civil War changed the lives of every American, including the Irish of Iowa. Beginning in April of 1861 and continuing without relief for the next four years, hundreds of thousands of men made the ultimate sacrifice in defense of the Union and the abolition of slavery. It was the ultimate measure of patriotism.

As the fighting began the war department put out a call for troops. Each state would be expected to send an allotment of young men and Iowa rose to the occasion. In fact, Iowa Gov. Samuel Kirkwood and State Adjutant General Nathanial Baker had more than a thousand volunteers ready for “immediate service” in only two days.

This impressive response filled Kirkwood with bravado. “I can raise 10,000 [recruits] in this State in twenty days,” he boasted. As war began, Iowa was gripped by war fever.

Even in Dubuque — a center of Irish voters in the state — there were enough volunteers in the first few weeks to fill the city quota. As early as January, the Dubuque City Guards, a local militia unit, informed Kirkwood that the men were ready to serve as the First Iowa Infantry at the governor’s call.

And yet Kirkwood and Baker were uneasy about the willingness of the Irish to support the call for troops. It was true that the Bishop of Dubuque, Clement Smyth, was vocal in his support for the Union cause. He spoke out often on the immorality of slavery, but he was countered by some Dubuquers who had racist beliefs and Southern sympathies.

And these dissenters were not beyond threatening the bishop himself! This hostility came home in dramatic fashion when the Smyth’s stable was burned to the ground. He also lost his carriage, two Morgan horses and a favored dog.

The most visible leader of the Irish hostility to the war was the editor of the Dubuque Herald, Dennis Mahony. An Irish born immigrant, Mahony had studied the law and practiced journalism in Philadelphia on his way to Iowa in 1843. On arrival in Dubuque County, he found work as a teacher and continued to study the law. Four years later, Mahony was admitted to the bar and appointed a justice of the peace for Jackson County.

Politics and journalism would be his life work. He served in the Iowa legislature for three terms beginning in 1848 and simultaneously was the editor of the Miner’s Express, a local newspaper. With three partners, Mahony moved on to publish and edit the Dubuque Herald. He would sell his interest in the paper in 1855, but repurchased his share in 1860.

Mahony’s return to journalism was something of a perfect storm for hostility toward President Abraham Lincoln and the Union cause. Passionate about politics and full of bombast, Mahony used the Herald as a bully pulpit to attack the Republican candidate during the fall. On Oct. 11, for example, he accused the Republican Party of plotting to unlawfully seize the rightful property of the citizenry of 15 states.

After Lincoln’s election in November, Mahony went on a vitriolic rant that was so laced with racist language that it makes the modern reader wince. There is no question that Mahony would use his paper and his political influence to oppose the Lincoln administration over the next four years.

TO READ THE ENTIRE STORY AND OTHER FASCINATING STORIES ABOUT IOWA HISTORY, subscribe to Iowa History Journal. You can also purchase back issues at the store.